SEXUAL CITIZENSHIP (www.glbtq.com 2004)

The concept of sexual citizenship was introduced in 1993 by David T. Evans. He wanted to amend social-constructionist theories of sexuality to underline the material foundation of sexualities from a neo-Marxist perspective. Nowadays, the concept, which has been developed mostly in Great Britain, is primarily used to draw attention to the political aspects of erotics and the sexual component of politics.

While one traditionally thinks of sexual expressions to be natural phenomena and private matters, they also have cultural and public aspects. Post-modernism, gender studies, and queer theory break down such dichotomies as culture/nature and public/private. Such is certainly true of sexual citizenship.

The concept of sexual citizenship bridges the private and public, and stresses the cultural and political sides of sexual expression. Sexual privacy cannot exist without open sexual cultures. Homosexuality might be consummated in the bedroom, but first partners must be found in the public space of streets, bars, and media such as newspapers and the internet.

Citizens have been defined in classical liberal theory as adult males operating in a free market. These men were seen abstractly, without sexuality or body. Using a broader concept of citizenship, however, its cultural, ethnic, gendered, and sexual facets can be emphasized. Citizens have genders, sexualities, and bodies that matter in politics. The rights of free expression, bodily autonomy, institutional inclusion, and spatial themes are all pertinent to the concept of sexual citizenship.

Free Sexual Expression

The right of free sexual expression especially concerns marginalized groups, such as women and sexual minorities. Many girls and women are dependent on fathers, husbands, or other figures of male authority, while gay men and lesbians are often condemned to the silence of the closet. They generally lack the civic right to express their sexual longings and experiences and are denied access to the media to do so.

Free expression of sexuality means that the public sphere, from schools to politics, cannot continue to be the privileged domain of male heterosexuality that it was in the past and mostly is in the present.

Pornography is a contested field of free expression. According to some, it is rooted in the exploitation of women and minors. Others, however, defend it as a legitimate form of sexual self-expression as long as the rights of the involved persons are respected, as in other domains of labor.

A special issue is age of consent. Countries have stipulated very different ages of consent in law, often restricting the erotic expression of "minors" and demonizing adults who violate the age boundary. At various times, some places had no age of consent, while others set it somewhere between 11 and 27 years, at the beginning of puberty or the time of marriage. Different limits were set for different activities, for example homo/heterosexual, married/unmarried, paid/unpaid.

Another issue concerns hate speech. Physicians, orthodox Christian, or Muslim leaders sometimes use the freedom of expression to attack gay men and lesbians by calling them sick, criminal, or worse than pigs or dogs. This name-calling is not only offensive to sexual minorities, but it affects their psychic and social well-being. It keeps a tradition of civic rejection alive. To curtail such insults, some states have created hate-speech laws.

Embodiment

Sexual citizenship also refers to embodiment. For women, it includes reproductive and contraceptive rights. It protects individual decisions in regard to birth control and abortion. For gay men and lesbians, embodiment concerns the freedom to engage in various kinds of sexual acts that may be prohibited by national and local authorities.

Criminal laws restrain access to sexuality by forbidding certain acts, restricting information, and banning imagery; by imposing ages of consent; or by making certain groups dependent on the authority of others. Public indecency laws, especially when they are selectively enforced, are typically used to proscribe erotic pleasure to gay men.

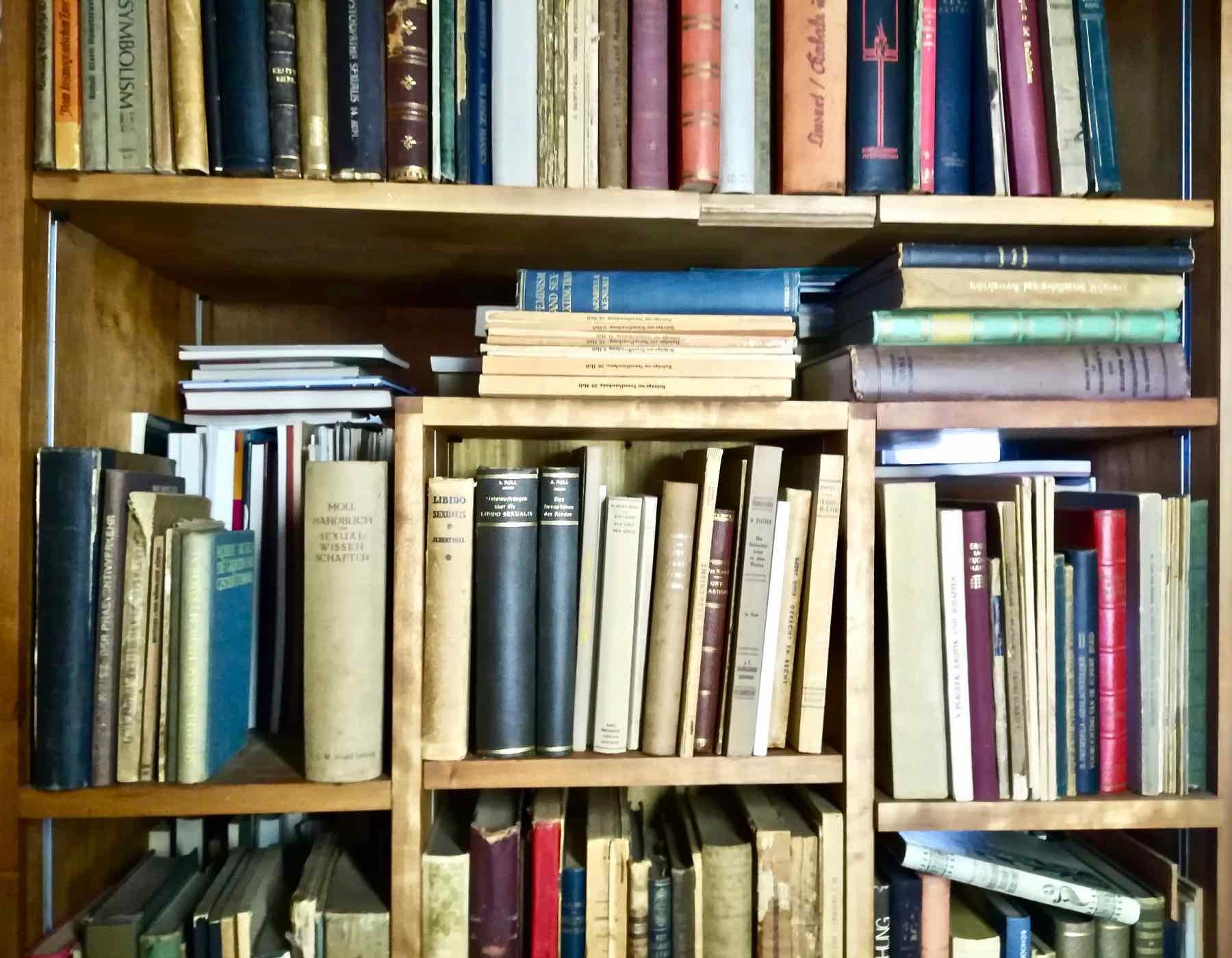

Medicine has added to bodily disempowerment by defining certain sexual practices as pathological, as it did with homosexuality and masturbation, and continues to do with other "paraphilias" (formerly called perversions) in the various updated diagnostic manuals of the psychiatric profession.

The medical profession has sometimes refused lesbians access to reproductive technologies because of their sexual preference. It has also attempted to impose unnecessary circumcision of boys.

The prevalence of various sexually transmitted diseases, in particular AIDS, have raised questions of access to medical care and pharmaceutical products, to accurate sex education, and to condoms. Denial of medical care, education, and protection endangers the lives of many sexually active people, both gay and straight.

Gender performance is another issue of sexual citizenship. It includes such aspects as sex reassignment surgery, gender transgression, and body transformation. Social reactions to gender deviant behavior often induce various kinds of violence and lead to the denial of basic rights, as, for example, the right to change sex legally.

Operations on intersexual children have been discussed in terms of genital mutilation. Desired body transformations for reasons of erotic pleasure have, on the other hand, been withheld. Laws, regulations, medical practices, and social prejudices continue to inhibit bodily expressions of sexual and gender variation.

Institutional Inclusion

Many institutions deny certain groups the opportunity to participate fully as sexual citizens. Examples include restricting the right to marry and prohibiting gay men and lesbians from serving in the military. Only a few, mostly European, countries have extended these rights to them.

Although some have argued that marriage is a private contract between citizens and should not be the state's business, refusal to allow same-sex couples to marry where other couples can do so constitutes discrimination. Moreover, many institutions privilege the nuclear family, which is a breach of sexual citizenship rights for all those who are outsiders to this social arrangement.

Denial of institutional and social equality and participation to sexual minorities also occurs in such areas as education, parental rights, health care, labor markets, housing, taxing, pensions and insurance, partner benefits, political representation, and immigration laws, to name only some of the major terrains. No country has accorded equality to all its citizens in all these areas; and most show little or no interest in doing so. The denial of institutional equality in these fields is a clear example that gay men and lesbians and other erotic groups are not fully recognized as citizens.

Spatial Themes

Another field of interest to sexual citizenship is that of space. Women, for example, have often been restrained to the private world of homes and families.

Gay men and lesbians are often restricted to a subculture of bars, usually located in decaying areas of cities. Even these locations are not safe for them, and they fail to be accorded the basic civil right of protection against abuse and violence.

Beyond these hidden and (semi)private places, the spatial interests of sexual citizens remain largely unacknowledged. Agency in public life is strongly limited by the sexism and homophobia of straight male society. Spatial claims of queers, for example, on public cruising or the establishment of gay venues, streets, and communities, remain contested, sometimes even in the gay world itself.

Visibility and safety in the public realm are prime concerns of queer activists. Going from the closet to the street means that gay men and lesbians need public space to express their sexual desires, to find partners, to debate politics, to demonstrate--in short, to enact their civic rights.

The Relative Importance of Sexual Citizenship

The various aspects of citizenship enable a comparison of the importance a society gives to each. For example, most Western countries value religious expression more than sexual expression. Although most democracies have separated state and church, old traditions remain strong. Religious citizenship continues to receive wide acknowledgement and to exert powerful influence in education and politics, while denial or neglect of sexual citizenship in such areas remains the norm.

Religious leaders who evoke anti-sexual traditions maintain a stronger foothold in civic society than leaders who speak out for sexual rights. Most churches uphold ideals of monogamous marriage, reproduction, and heterosexuality, at most giving a small "place at the table" to non-heterosexual individuals.

A Global Perspective

Sexual politics is a minor theme in the Western democracies and remains even more marginal in most other places. Sexual rights are denied to women and erotic communities in most Muslim and African countries. They are often neglected in Asian and Latin-American nations.

Only a few states outside the European Union have been actively involved in extending civil rights to gay men and lesbians. Among them are South Africa, Brazil, Mexico, Canada, Australia, and the United States. Other countries that had no anti-homosexual criminal laws, such as Japan and Thailand, have been slow to offer safeguards to sexual communities in civil law. Rights given to gays and lesbians are rarely extended to transgendered individuals or sadomasochists and never to pedophiles.

Even in most places where gay men and lesbians have achieved legal protection, the social climate remains antagonistic. In those countries, issues of sexual citizenship have moved from law reform and erasure of institutional intimidation to education, equal representation, visibility, and spatial claims.

In some European countries where the most blatant forms of sexual discrimination have disappeared, it has become difficult to mobilize gay and lesbian populations to fight for rights of sexual citizenship. The change from legal to social emancipation, where goals are more difficult to define, has diminished interest in sexual activism.

The concept of sexual citizenship draws our attention to all kinds of social exclusions that the various sexual communities experience. These exclusions inhibit their political, social, cultural, and economic participation. The various constraints point to the necessity of queering all kinds of institutions. Simply allowing sexual minorities into these organizations on an individual basis does not challenge the heterosexist assumptions that govern most societies.

Sexual citizenship refers to the transformation of public life into a domain that is no longer dominated by male heterosexuals, but that is based in gender and sexual diversity. The goal is a society in which diverse people can take responsibility for their own sexual lives.

Literature:

Bell, David, and John Binnie. The Sexual Citizen: Queer Politics and Beyond. Cambridge, England: Polity, 2000.

Blasius, Mark, ed. Sexual Identities, Queer Politics. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Clarke, Eric. Virtuous Vice: Homoeroticism and Public Sphere. Durham, N. C.: Duke University Press, 2000.

Evans, David T. Sexual Citizenship: The Material Construction of Sexualities. London: Routledge, 1993.

Kaplan, Morris. Sexual Justice: Democratic Citizenship and the Politics of Desire. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Lister, Ruth. "Sexual Citizenship." Handbook of Citizenship Studies. F. Isin Engin and Bryan S. Turner, eds. London: Sage, 2002. 191-207.

Parker, Richard, Regina M. Barbosa, and Peter Aggleton, eds. Framing the Sexual Subject: The Politics of Gender, Sexuality and Power. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Richardson, Diane. Rethinking Sexuality. London: Sage, 2000.

Weeks, Jeffrey. "The Sexual Citizen." Theory, Culture and Society 15.3-4 (1998): 35-52.